By John Helmer, Moscow

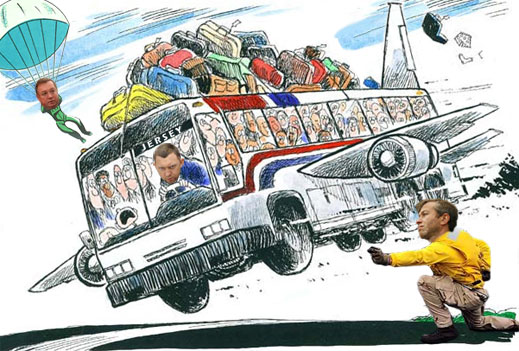

Oleg Deripaska (image centre) is not having a good week. It started more or less out of harm’s way with a report in a London magazine, Private Eye. This claims that at least two Caribbean companies and one UK entity, which Deripaska uses to channel sales revenues from United Company Rusal to beneficiaries and places other than the shareholder income line on the company’s audited balance-sheet, “have been identified by economic crime specialists as fronts for extensive laundering – of proceeds for illicit arms exports, drugs, counterfeiting, corrupt public contracts, and much else.”

Then there was the collapse of the first Deripaska company to fall into official bankruptcy – Kuban Airlines – largely, aviation industry sources say, on account of lack of capital on the part of the owner to raise the operating margin of aircraft, and the risk of continuing to fly unsafe aircraft on domestic routes when they are banned internationally.

And finally, there was the first-ever speech by President Vladimir Putin, in front of the Russian parliament, attacking Russian abuse of offshore corporate vehicles such as UC Rusal, a Jersey-registered entity. According to Putin, “the offshore nature of Russia’s economy has become a household word. Experts call this escaping the jurisdiction. We need a comprehensive system of measures for the deoffshorization of our economy.”

The good news for Deripaska is that according to a release on Thursday by the Accounting Chamber, headed by Sergei Stepashin (image left), President Putin’s proposed change on policy towards offshore accounting may not come to anything.

There is no longer any reference on the website of the Deripaska holding, Basic Element, to Kuban Airlines. But there is a long history of failed ambition on Deripaska’s part to build an aircraft business, from manufacturing the aluminium for the airframes, to constructing Tupolev and Antonov designs at the Aviacor works in Samara, to operating a commercial airline fleet, as well as the airports and jet fuel terminals to service them.

Aviacor, which had been part of the Tupolev chain of production and service during the Soviet era, could not persuade Chinese airlines to retain their old Tupolev aircraft. So Deripaska tried persuading the Australian government to buy the An-140 for flying doctor and remote regional air service. When that didn’t work, Deripaska worked on the Russian government to support the An-140 production line. The Defense Ministry has started spending budget money to pay Deripaska for the aircraft. A similar effort to induce the Aeroflot board to allow commercial funds for the Deripaska turboprops has yet to hit paydirt.

Aviacor, which had been part of the Tupolev chain of production and service during the Soviet era, could not persuade Chinese airlines to retain their old Tupolev aircraft. So Deripaska tried persuading the Australian government to buy the An-140 for flying doctor and remote regional air service. When that didn’t work, Deripaska worked on the Russian government to support the An-140 production line. The Defense Ministry has started spending budget money to pay Deripaska for the aircraft. A similar effort to induce the Aeroflot board to allow commercial funds for the Deripaska turboprops has yet to hit paydirt.

Kuban Airlines has been less successful in getting state subsidies to stay in the air. On December 11, with debts of at least Rb5 billion ($161 million), the airline said it was halting operations. In the lurch are 14,500 passengers who have paid the equivalent of about $15 million for tickets to nowhere. Vnukovo and other airport fuel providers are owed less – about $10 million. Until the airline appears in the Arbitrazh Court and a bankruptcy administrator is appointed, it isn’t known how much Kuban Airlines owes to banks and aircraft leasing companies for its operating fleet – three Boeing 737s and three Airbus A319s.

In a public statement, Sergei Mordvintsev, the chief executive of Kuban Airlines, claims it was the Russian government which drove the company into bankruptcy. This, he explained, is because new regulations, introduced on November 25, require air carriers to be certified to operate not less than eight aircraft with passenger capacity of more than 55 seats.

Unmentioned by Mordvintsev is the reluctance on Deripaska’s part to make the capital injection required to bring the airline’s fleet up to certifiable standard. Because it was unable to pay for its Airbuses, they had already been returned to the leasors. That was a 50% cut in safe-operating fleet. The coffin-class, Yakovlev Yak-42 aircraft, was withdrawn from operations in November after its safe operating record had led to sanctions from the domestic Russian regulator. There had been earlier safety reviews of the Yak, but they intensified after the September 2011 crash at Yaroslavl, which killed the Locomotiv ice-hockey team and 8 crew. That incident has subsequently been blamed on pilot error.

Eight Yak-42s had been the mainstay of the Kuban Airlines fleet, but from the start of 2011 were to have been withdrawn and replaced by Boeing and Airbus aircraft. It isn’t known what Deripaska, Basic Element, or Kuban Airlines had done to persuade the domestic regulators to certify the plane as safe for operations after five of its Yak-42 aircraft were banned in Europe from November 2009. That meant that most of the fleet were disallowed from operating the profitable international charter line of business. Domestically, the rising cost of fuel and regional competition put a squeeze on how much the airline could charge passengers.

Aviation industry analysts in Moscow are not surprised that Kuban Airlines has gone belly up, but they dispute where the blame lies. Alexei Astanov of Gazprombank said the real reason for the bankruptcy wasn’t the new fleet certification requirement. Rather, the company had been working on a low-margin of profitability with aircraft which could no longer be operated, and it lacked the cashflow to support an upgraded fleet of imported aircraft. According to Konstantin Yuminov from Raiffeisen Bank, without funding from Deripaska’s holding, Kuban Airlines was ill-equipped to compete on the same southwestern regional air routes with DonAvia, a subsidiary of Aeroflot. Andrei Shenk, an analyst at Invest Café, added: “The RosAviation [certification] measures are not the main reason. The main one is their bad financial conditions, and these certification measures were the catalyst. There were debts to creditors. Older models of aircraft consumed more fuel. The reason for bankruptcy is complex. Market conditions do not allow it to operate due to the lease payments and the competition.”

During the last economic downturn, in 2008-2009, Rusal, the cash cow of the Deripaska group, was itself on the verge of bankruptcy. Between November 1, 2008, and May 31, 2009, a total of 144 payment claims were filed against Rusal in the Russian Arbitrazh Court system; that made an average of 1.1 cases per day. The biggest of the claimants was Russian Railways for freight charges Rusal had stopped paying.

A Rusal lawyer at the time explained that technically Deripaska was operating the company while it was insolvent. To conserve cash, Rusal stopped paying creditors and lawyers were instructed to protract court actions for as long as possible.

Parallel claims totalling more than 277 were filed against other companies in the Deripaska holding. The tactics there too were to delay payment and stall recovery in the courts. Alfa Bank, under Mikhail Fridman, came closest to filing in court to have Rusal declared bankrupt and new management appointed to supervise its cashflow, but government officials including then President Dmitry Medvedev, warned him off.

But since Rusal was the source of most of the cash that financed relatively weak businesses, like Aviacor and Kuban Airlines, any increase of financial pressure at Rusal was bound to intensify the cash shortage elsewhere in the Deripaska group. The problem which the arbitrazh court system has not been able to address, nor the creditors of Deripaska companies other than Rusal, is that there is no telling quite where Rusal’s revenues for the sale of aluminium go.

The operation of offshore haven companies and the Latvian banking system for redirecting metal sale revenues outside Rusal’s record-keeping and its shareholders’ knowledge has been reported in part already. Maxberg Limited Liability Partnership (LLP), for example, turns out to have been a UK-registered conduit for millions of dollars of aluminium sale revenues, paying no tax, and subject to two Caribbean directorships, Milltown Corporate Services and Ireland & Overseas Acquisitions which, according to the latest London investigation, originated with a Dublin firm of company formation experts. The records show that while Deripaska operated Maxberg, the similarly named Cliffberg was operated by others. Inhold, a Bahamas entity appears on the directors’ list of Maxberg in 2011, while Intrahold and Monhold appear on the Seychelles register to be directing LLPs of similar structure and purpose to Maxberg’s.

According to the Private Eye report, the LLP structure was introduced in UK law a decade ago “at the behest of the big accountancy firms which wanted to limit their liabilities for dodgy audits but remain partnerships largely for the tax advantages.” They are exempt under the UK rules from having to file tax returns; to reveal who owns them; or to require individuals as directors. Most LLPs – there are 50,000 of them now on the UK register — are relieved from having their accounts audited.

President Vladimir Putin appears to understand what’s going on, and also why. In his December 12 speech to the Federal Assembly of both chambers of parliament, he criticized the “offshore nature of the Russian economy. Experts call this phenomenon a flight from the jurisdiction. By some estimates, nine out of ten significant transactions made by major Russian companies, including, by the way, companies with state participation, are not governed by domestic law. We need a whole system of measures of deoffshorization of our economy. I instruct the Government to make appropriate proposals on this complex issue.

“It is necessary to achieve the transparency of offshore companies, [and the] disclosure of tax information, as is done by many countries in the negotiation process with offshore zones and in the signing of the relevant agreements. This can and should be done.” That sounds like a presidential clean-up order – not good for Deripaska, Rusal and fronts like Maxberg.

So what has been done by the Accounting Chamber in checking the offshore operations of Rusal?

The chamber investigation had been requested during a debate at the State Duma last March, when deputy Andrei Krutov, charged Rusal with offshore tax and money-laundering offences, and requested Stepashin’s investigation. Rusal responded immediately with a threat to charge Krutov with a criminal offence. “Andrei Krutov’s recent and frequent comments in relation to UC RUSAL are distorted and incorrect and clearly demonstrate that he does not have any information about the situation at the Company’s facilities. As a result, the Company is examining possible legal action regarding disseminating false information. RUSAL operates in full compliance with the current tax legislation of the Russian Federation.”

Since July the chamber has been investigating Rusal’s offshore operations. The check was carried out by two chamber auditors, Igor Vasiliev and Sergei Ryabukhin.

Yesterday the Chamber issued a public statement of the results. The statement acknowledges Krutov’s charges, and admits the investigation has focused on the use of tolling contracts for domestic processing of aluminium, and on offshore channels for export-import operations.

The conclusion, says the chamber, is “a number of negative factors on the most important economic and social interests of the Russian Federation.”

“The use of tolling does not stimulate the development of Russian enterprises in the direction of further manufacture of products intended for the domestic consumer… In the practice of foreign trade participants with still widely used contracts with offshore companies, all the goods on it are sent from the Russian Federation not into listed offshore zones, but to the third countries. The use of such contracts can shift the base for taxation of profits to countries with low levels of taxation.”

“In more than 22% of single-industry [Russian] municipalities, town-forming enterprises are involved in export-import activity for contracts with entities registered in offshore zones. This results in the transfer base for profits tax to foreign low-tax territory, reducing taxes in the consolidated budget of the Russian Federation, and thus does not contribute to maintaining a stable financial situation in these areas… In the submissions for the Collegium [by the analysts], it is noted that the current situation with the use of offshore companies indicates the need to change the existing mechanism of taxation, in order to create tax incentives for organizations to move from offshore to the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation and to provide consolidated revenues [on the company balance sheet].”

There is no finding that Rusal has violated Russia’s transfer pricing regulations or has violated any Russian tax rule. Stepashin also parachutes away from the problem of what is to be done next. The Chamber, according to the statement, “decided to send informational letters to Russian President Vladimir Putin and the Federal Customs Service. The Audit report is sent to the chambers of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation and the deputy of the State Duma of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation, A.D.Krutov.”

If Stepashin and Putin continue passing the buck to each other in this fashion, then who is in charge of cashflow control now? Is Roman Abramovich (image right) to be the signalman for where Rusal’s cash should go in future? Norilsk Nickel’s too.

Leave a Reply