By John Helmer, Moscow

![]() @bears_with

@bears_with

What can Foreign Affairs, bimonthly tribune of the Council of Foreign Affairs in New York, be referring to when it reported on the government for which “in worldview and practice, it was a conspiracy that perceived conspiracy everywhere and in everything, constantly gaslighting itself. In administration, it constituted a crusade for planning and control that ended up generating a proliferation of improvised illegalities, a perverse drive for order, and a system in which propaganda and myths about ‘the system’ were the most systematized part.”

Need a clue? On the head of government’s left foot two of his toes were webbed. Still stumped?

According to Stephen Kotkin’s report in Foreign Affairs entitled “When Stalin Faced Hitler, Who Fooled Whom?”, Joseph Stalin had “thick, discolored toenails on his right foot, and the two webbed toes on his left foot (an omen, in traditional Russian folklore, of Satanic influence).” The government which “was a conspiracy that perceived conspiracy everywhere and in everything” wasn’t the US Deep State, as familiar as that is these days. It was Stalin’s Russia, according to Kotkin (“dear cat” is the translation of his Russian name).

At the start of more than two thousand pages of his history of Stalin’s life, Kotkin also reports “the young Stalin had a penis and he used it”. Kotkin uses sexual innuendo throughout the book to discredit everyone Kotkin comes across in the Bolshevik movement: if Russian penises pointed leftwards, Kotkin points them out. The Lena goldfields strike of March 1912, followed by a police massacre of miners, Kotkin puts down to “rancid horse penises sold as meat at the company store”.

Kotkin’s account of Stalin’s penis during his four-year sentence to exile in northwestern Siberia from 1914, is reported for his “engag[ing] in the exiled revolutionary pastime of seducing and abandoning peasant girls”. Kotkin is neither human nor animal rights advocate when he records “Stalin would later recall his dog in Siberia, Tishka, but not his female companions and bastards”. Rasputin, on other hand, emerges from Kotkin’s research “to smell like a goat…and to screw [sic] like one, too.”

Left to right: Tsar Nicholas II with a favourite dog; Vladimir Lenin with his pet cat; Stalin has given his name to a Russian-bred combination of Airedale, Schnauzer, Rottweiler, and Caucasian Shepherd. No genuine photograph can be found of Stalin himself with the so-called Black Terrier or of its predecessor, Tishka.

By contrast, Kotkin endorses the phallic qualities of Pyotr Durnovo (in Russian the name means “bad”), Tsar Nicholas II’s favourite interior minister who from 1905 to 1906 directed systematic repression of all dissent across the empire. Kotkin acknowledges that Durnovo had a wandering penis, particularly when it was covered with a police uniform, but Kotkin celebrates him nonetheless. “Durnovo showed initiative [emphasis Kotkin’s]…This is one of those moments in the play of large-scale historical structures when personality proved decisive: a lesser interior minister could not have managed…it is impossible to know what would have transpired had Durnovo’s exceptional resoluteness and police skill not saved tsarism in 1905-6. Still, one [sic] wonders whether the history of one sixth of the earth, and beyond, would have been as catastrophic, and would have seen the appearance of Stalin’s inordinately violent dictatorship.”

This form of counterfactual history is repeated for two thousand pages, regularly to Stalin’s disadvantage. For example, “the Bolshevik putsch could have been prevented by a couple of bullets”; “had Tsaritsyn fallen that autumn of 1918, [Stalin] might have faced a government inquiry and disciplinary action, as well as permanent reputational damage”; “had Lenin allowed Stalin and his band a complete victory over Trotsky in July 1919, the outcome of the other battle – the civil war against the Whites – might have turned out differently”.

But Kotkin’s counterfactual method has its limits. It begs the question Kotkin has not asked himself: what if Stalin and Durnovo had both been born without penises?

Left and centre: Volume One and Volume Two of Kotkin’s biography of Stalin: https://www.amazon.com/Stalin- Right: Kotkin sells advice on Russia and China to investment fund managers, calling himself “a renowned specialist in communist regimes”. A sample: “globalisation is not Westernisation, China didn’t become like the US, and it’s not going to, it’s China. It has its own civilisation, its own institutional legacies.” Kotkin also describes himself as a consultant to “philanthropic institutions, such as George Soros' Open Society Foundations”.

A few paragraphs later after Kotkin’s, I mean Stalin’s penis makes its debut – page 9, with 948 pages still to go of Volume One; another 1,184 pages in Volume Two – Kotkin also judges that Stalin was a “narcissist”. This, he explains, he doesn’t mean in the psycho-analytical sense because in Kotkin’s vocabulary – it’s “another word for a professional revolutionary”. What follows over several hundred pages are retellings of Stalin’s early career – seminary choir, publication of poetry, plant and mine strikes, rally speeches, pamphleteering, armed robbery, assassination plots, arrests, seventeen years of prison sentences, before his membership of the Bolshevik executive committee on the eve of the revolution in November 1917.

If long, hard, risky work with hundreds of people speaking multiple languages makes the symptomatology for narcissism, Kotkin might just as well have said the diagnostic term applies to professors at Princeton University, where Kotkin is employed on a stipend bequeathed by John Birkelund, a former US naval intelligence officer who operated in Berlin and Warsaw before turning New York banker specializing in corporate asset raids. Kotkin dedicates the first Stalin volume to Birkelund whom he calls “businessman, benefactor, fellow historian”.

All sorts of one-term pejoratives are placed by Kotkin throughout his history – at everybody but himself. “Derivative” is another one, consistently applied by Kotkin to whatever paper Stalin managed to write for publication; never to the stories Kotkin lifts from other researchers, with or without footnotes, the list of which Kotkin reproduces over 121 pages of Volume 1, each filled with three columns of minuscule print.

Seeds planted, you might say, until the final page when they become a harvest which identifies only one man, though he isn’t Stalin.

Stalin, concludes Kotkin on his last page, “was uncommonly skilful in building an awesome dictatorship, but also a bungler, getting fascism wrong, stumbling in foreign policy. But he had will. He went to Siberia in January 1928 and did not look back. History, for better and for worse, is made by those who never give up.” With that concluding tautology, Kotkin pronounces on himself. The narcissist who retells Russian history to Americans who never give up – that’s to say, never give up their obsession with their Russian enemy.

In Volume One, for example, Kotkin identifies his selection of four turning-points in Stalin’s rise to power from oblivion, between the pinnacle and the dust-bin of history. The first was in January 1912, when the Bolsheviks gathered in Prague to elect a new central executive committee, to which Stalin was appointed. “This is exactly the kind of person I need!” Lenin was reported to have told Stalin’s detractors at the time. The second was the four-year period of World War 1, when Kotkin, repeating Trotsky, notes that “Stalin published absolutely nothing of consequence during the greatest conflioct of world history…The future arbiter all thought left no wartime thoughts whatsoever, not even a diary.”

The third turning-point was the year of 1917 when Kotkin concludes his man was “deeply engaged in all deliberations and actions in the innermost circle of the Bolshevik leadership, and, as the coup neared and then took place, he was observed in the thick of events.” In that thick, Kotkin can’t miss Stalin’s penis. In the spring of 1917, for example, he “took advantage of their communal-style living arrangements to steal [Vyacheslav] Molotov’s girlfriend.” Then weeks later, to avoid the police, Stalin moved beds to the apartment of the Alliluyev family where he “may have had a liaison” with mother Olga Alliluyeva; and then when reading bedtime stories to her daughters Nadezhda and Anna, he “charm[ed] the girls right through their nightshirts”.

The fourth of Kotkin’s turning-points is Lenin’s posting of Stalin to Tsaritsyn (Volgograd, Stalingrad), at the civil war’s southern front in June 1918. Stalin’s assignment was a combination of military operations, grain requisitioning for the northern capital and Red Army, and securing Volga region power for the Bolsheviks. There the rivalry between Stalin and Trotsky reached such an intensity that Lenin recalled them both. For Kotkin, though, this was Stalin’s first high-profile exercise of power. He reports he “donned a collarless tunic – the quasi-military style of attire made famous by Kerensky – and ordered a local cobbler to fashion him a pair of high black boots.” Combining symptoms of “derivative” with “narcissism”, Stalin had become, diagnoses Kotkin, “the swaggering cobbler’s son”.

Noone before or after has ever described Stalin as walking with a swagger; on the contrary, from an early injury to his legs he limped and tried to conceal the deformity. Kotkin also fails to get the details of the tunic right. It was not collarless, and its public recognition began in the tsarist army. During World War I Russian officers called it a French (in Russian, френч) after the best known of its wearers, the British commander in France, Field Marshal Sir John French.

In poring through the old Tsaritsyn records, Kotkin hasn’t managed to find evidence that Stalin opened his Kerensky-derived pants to the local girls. However, Kotkin can’t help exposing his own paedophile innuendo. When Stalin arrived in Tsaritsyn, he “also had his teenage wife, Nadya [Nadezhda Alliluyeva] in tow.” Nadezhda, Kotkin omits, had her 18th birthday in Tsaritsyn. Kotkin leaves in that “she wore a military tunic and worked in his traveling ‘secretariat’”. The commas are Kotkin’s inversion.

Joseph Stalin in tunic and Nadezhda Alliluyeva in dress, photographed in about 1917.

In Kotkin’s re-telling, the stories are all cribbed from Russian and other sources. Kotkin adds nothing fresh except for innuendo and sarcasm directed at Stalin’s role, along with every other Bolshevik he can name. This is especially telling in Kotkin’s account of the tumult of the first post–revolutionary year of 1918. By what moral standard, for example, does Kotkin inform that when the Bolshevik administration moved the Russian capital from St. Petersburg to Moscow, and took over the Metropole Hotel, men lodged with their “mistresses”. Kotkin tries the innuendo that Nikolai Bukharin “who lived there, as did his future lover Anna Larina, then a child (they met when she was four and he, twenty-nine)” was a paedophile.

By what policy standard does he judge Stalin’s initial assessment of the Brest-Litovsk terms dictated by the Germans in February 1918, was “vacillation” for expressing the suspicion “the Germans are provoking us into a refusal”.

What standard of etiquette does Kotkin claim to uphold when condemning Karl Radek, one of the Bolshevik negotiators at the first round of armistice negotiations with the Germans, including (Kotkin itemizes) a baron, a major general and a field marshal prince – Radek is reported as leaning forward on his side of the table and “blew smoke”?

The answer is that Kotkin’s standard is pervasive in its explicit, implicit, and also snide condemnations of everything the Bolsheviks said or did, including Stalin. But this is Kotkin’s personal standard, not one he substantiates with the evidence he has accumulated from everyone who has gone before him, let alone his own research. It’s a standard of personal, if not ethnic exceptionalism. Kotkin starts the work with the declaration of “American power greater than any other in world history” and combines it with sexual fetishism. How much smoke or mistresses Americans blew as they acquired “power greater than any other in world history” is not a standard in Kotkin’s global moral scheme. In that scheme American power-getting is moral; Russian power-getting is not. What’s the point of two thousand pages of this, especially now when the US is at war with Russia? Is Kotkin’s point nothing more than a war cry?

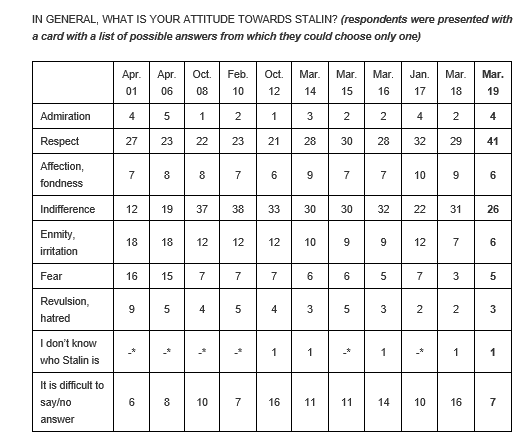

The latest opinion polls suggest, not only that there is no audience among Russians for Kotkin’s version of Stalin. They also show that young Russians are not more persuaded of the Americanized version of his role than older Russians who remember the last years of Stalin’s rule until his death in 1953. Time, at least time in Russia, is telling against Kotkin by increasing indifference among the young, and overall, by increasing positive sentiment towards Stalin; it’s now the majority view for the first time in twenty years. The reason for this is not that historians have made Stalin’s negatives and positives clearer to Russians. It’s because Russia is once more under attack: the Russian reaction is to remember the role Stalin played in defeating the last one.

The most recent nationwide polling of Russian opinion towards Stalin was conducted at the end of March, and published by the Levada Centre on April 19. Click to read in full. Negative sentiment has dwindled significantly; positive sentiment seesaws with indifference.

Source: https://www.levada.ru

At the end of Volume One Kotkin asks what would have happened if Stalin had died in one of his brushes with death – smallpox in 1884; road accident in 1890; typhus in 1909; tuberculosis in 1915; appendicitis in 1921. Kotkin answers himself: “the forced wholesale collectivization – the only kind – would have been near zero, and the likelihood that the Soviet regime would have been transformed into something else or fallen apart would have been high.” This is unerring stuff – between those two counterfactuals, no possibility for any historian to make a mistake.

With analysis of this quality, the bigger question to ask is what if Kotkin had died before starting his story of Stalin. Would Kotkin’s Princeton students or his hedge fund clients be poorer or richer if Kotkin’s Stalin had never existed – only the Russian one?

NOTE: Kotkin’s first volume has now been in print since 2014; the second volume since October 2017. The most thorough analysis in English, a highly critical one, has been published in four parts by Fred Williams in the World Socialist Website, a Trotsky partisan journal. The Williams series can be read starting here. In Russia Kotkin has been promoted in a direct interview by the US Government radio and website, Svoboda. This is remarkable for confirming what Williams reported earlier as suspecting -- that Kotkin cannot speak Russian; Svoboda uses a Russian voiceover to translate his English answers into Russian for the radio audience. In Williams’s analysis, Kotkin’s incapacity in Russian is a pointer to further and fundamental failures of research method, analysis of evidence, and truth-telling. Just how badly Kotkin pronounces Russian when speaking in English can also be gauged from his attempt in this New York bookshop interview with Keith (“I’ve always rooted for the Bolsheviks to lose”) Gessen. Listen at Minute 17:20 when Kotkin says DER-NEW-VOH, mispronouncing the name of the tsarist interior minister, a hero in his book, Ivan Durnovo. No Russian, not even Gessen, could pronounce that name as Kotkin does. And another thing: not a single Russian expert on Stalin nor a Russian historian has published a review of Kotkin’s books. Not one. The only review to be found in the Russian language comes from a Moldovan, Vladimir Solonari, who teaches at the University of Central Florida.

Leave a Reply